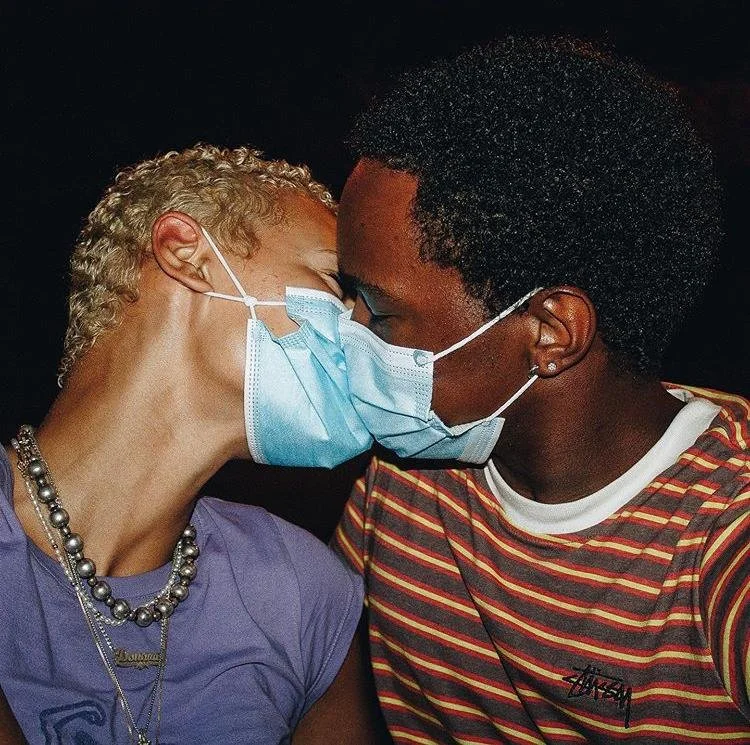

love in the time of coronavirus

How dating apps can respond to emerging cultural shifts

Since the launch of Tinder in 2012, dating apps have become notorious for their facilitation of superficial, rapid exchanges via app-based text messaging, giving way to a new digital age of hook-up culture. Colloquial terms such as ‘ghosting’, ‘orbiting’ and ‘breadcrumbing’ emerged as handy lexicon for a dating world that was plagued with the issue of partner disposability by the very nature of the virtual dating medium and its dehumanising anonymisation of individuals. The very semiotic nature of the conventional dating app – be it Tinder, Bumble or Grindr – sets up partner potentials as swipeable commodities: users are displayed via quick-view profiles focusing on photographic appearance, with more detailed bio information only visible to those who care to click through past initial display pictures. Like a game, users swipe left to discard a partner potential, or swipe right to make a match, allowing for speedy efficiency in sifting through the endless sea of possibilities available through the app algorithm.

From Swift Contact to Prolonged Courtship

The Covid-19 outbreak, however, brought this high-octane hook-up culture to a halt, as countries across the globe went into lockdown and dating app users were left with no option but to engage in more meaningful, prolonged communication with their online love potentials – or as one Twitter user put it, people were being forced to ‘Jane Austen it up’.

And so they did: according to the Economist, between February and March 2020, the average conversation length on Tinder rose by 25%. And Bumble, who had introduced a video chat feature in 2019, found an 84% increase in video calls in March this year, with video calls lasting an average of 28 minutes. The coronavirus gave way to a new age of courtship, as app users shifted away from contact towards communication. The distinction between the two forms of interaction is key when considering the growing popularity of video chat features (Hinge, the League and Match released video features shortly after the pandemic hit, and the majority of OkCupid users have stated that they plan to continue using video after the virus subsides). Unlike text-based messaging, which allows for contact (i.e. short message exchanges), video chat is (quite obviously) a semiotically richer environment that facilitates a sustained interaction of feedback and response, which is crucial to establishing real communication. Beyond video chat, other new features such as voice notes are further aiding the return of slow, engaged courtship in the digital age.

A key point to note is that the shift towards courtship culture is not purely a result of the pandemic. Rather, the coronavirus merely sped up a process that was already taking shape in wider culture. If the cult popularity of Love Island over previous years epitomised the former dominance of hook-up culture, emphasis on visual appearance (over personhood), and superficial, disposable romantic interactions – then the arrival of this year’s Netflix hit, Love is Blind, was symptomatic of a growing fatigue with digital dating culture, and the emergent interest in ‘slow dating’. A reality TV show where contestants enter ‘pods’ to talk with potential love matches – albeit without seeing or physically touching them – Love is Blind centres around communication, intimate bonding, and ultimately, serious courtship: the end goal is to become engaged, and hopefully married, to another participant. Where Love Island indulged in promiscuity, Love is Blind now reflects a growing cultural interest in romantic commitment.

how can dating apps respond through UX design?

A key hindrance to romantic courtship in dating apps is the dehumanising and anonymising effects of the digital medium in itself, as well as the use of conventional UX designs which emphasise limitless availability, swipeability, and physical appearance. As such, dating apps may look to wider culture and emergent competitors to identify visual and linguistic cues that bring tangibility and personhood back into the love equation.

An app leading the vanguard on this front is Lex, which describes itself as “a lo-fi, text-based dating and social app for womxn, trans, genderqueer, two spirit, and non-binary people for meeting lovers and friends.” Short for ‘lexicon’ – the app name in itself is founded upon the idea of verbal communication. Within the app design, Lex manages to disrupt the digital dating category, aligning with emergent dating culture by coding analogue tangibility, personhood, and engaged communication.

Firstly, the app uses serifed typography (rather than sans serif, which is associated with the digital realm), in order to visually connote analogue print. Further to this, the app reads as a feed of text-based classified ads, with titles and descriptions written by each user, evoking the nostalgia of newspaper personal ads. In fact, it was this retro medium that inspired Lex, which started out as an Instagram account featuring extracts of personals sourced from vintage female-led erotica magazines. The tangibility communicated through Lex’s text-based ads and serifed typography therefore grounds users in physical reality, combatting the anonymising effects of highly digital aesthetics.

The absence of photographs, with an emphasis on descriptive text, also allows Lex to code users’ personhood, as their personality and interests are brought to the forefront (rather than their physical appearance). Personhood is also coded through another key feature of the Lex UX experience: one has to gently scroll along as they read written ads (rather than swiftly swiping), and actively click through in order to message any love potentials who strike an appeal. This therefore draws attention to the process of thoughtfully engaging with other users, away from the usual process of continuously discarding unwanted matches, as in mainstream apps.

Finally, the text-based personal ad format in itself fosters engaged communication, as users are forced to grapple with the slow, mindful process of writing and elaborating an ad that aptly expresses their interests, personality, and desires. Additionally, Lex requires users to commit to respectful, hate-free interactions when signing up (see their RULES OF CONDUCT), resulting in a deeply supportive, community-oriented dating platform.

Lex aptly demonstrates how other dating apps can borrow visual and linguistic cues from wider culture (e.g. newspaper personal ads) in order to respond to emerging cultural attitudes towards love and dating. While the rising popularity of slow dating and courtship by no way means an end to the judgement-free liberation brought about by hook-up culture, dating apps can certainly make for more inclusive platforms that accommodate and facilitate all styles of dating.

Originally published here by Sign Salad, a leading London-based cultural foresight agency specialising in semiotics and language analysis.